Even though she seemed quite useless during the bigger part of our tour, Eghi did a very good job in saving the trip when the rear axis of our car broke in the middle of nowhere. It was only the fourth day and already we were forced to leave the tour's rigid schedule for almost two days. With just a few phone calls she put us up at a nomadic family's camp just a few hundred meters off the road. Thanks to her we will remember these two days as the most exciting time on that 18-day trip. We stayed with the family and a bunch of their friends in their two gers while the agency sent a new rear axis from Ulaanbaatar. While the locals slept in the bed- and living room gear with about 15 people, the six of us got cozy in the smaller kitchen gear. The two days that followed put us right in the middle of the nomadic lifestyle that many Mongolians still live today.

This included consuming all sorts of weird dairy products that they made out of cow-, goat-, sheep- and horse milk and that were, let's be honest here, brakish, at least for our Western European tastebuds; it included eating overcooked mutton, blood sausage and various other animal parts that were even more unbearable to put in our mouths; it included playing Mongolian games with the family's children; it included witnessing how their older boys rounded up an immense herd of about a thousand sheep and goats for the night and milking them in the morning; and, most remarkably, it included driving out into the desert and getting insanely drunk with the family's dad and his friend. It started out with sharing stories and music in the limelight of the jeep's headlights, with having a few beers and a few vodka shots. Then we realized that Mongolians drink beer like lemonade and vodka like beer. To cut a long story short: that night we slept in the car out in the open desert as nobody was fit to drive, not even on an empty field.

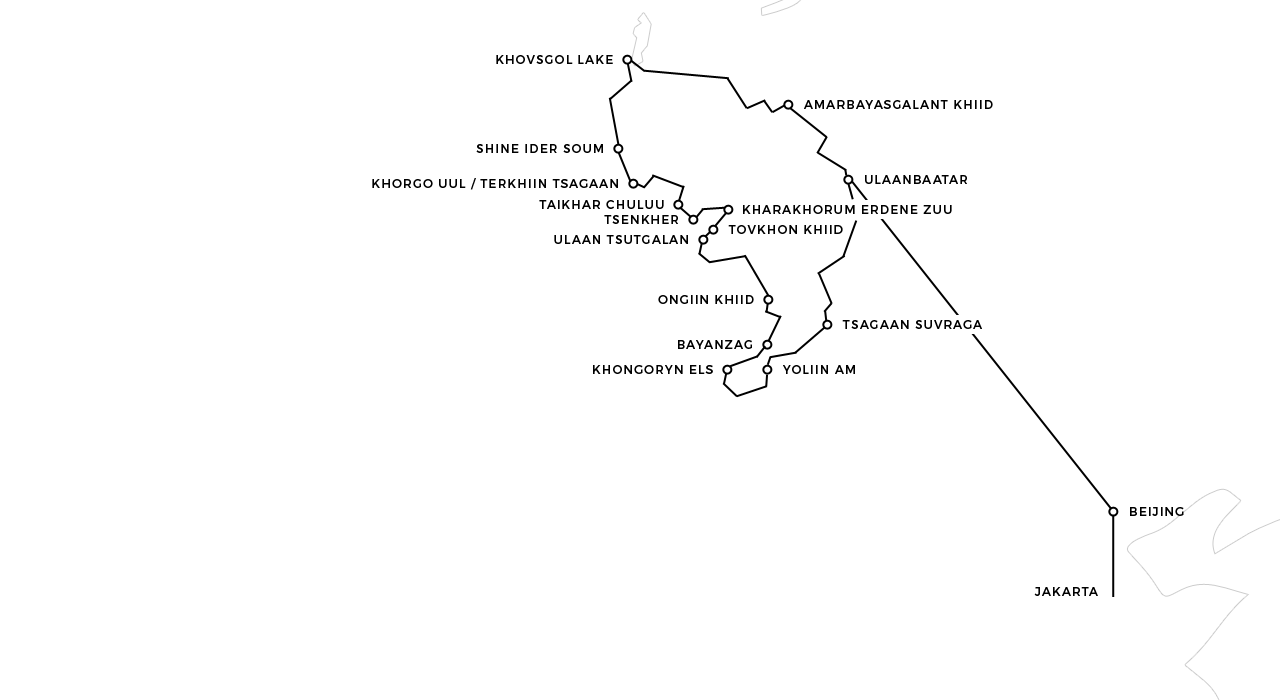

Although this experience was without a doubt the closest encounter we had with the local nomads, we stayed with Mongolian families almost every night on that 18-day trip. To make some extra money over the three months of summer, many of these families had put up a few additional gers to host tourists. How the tour agencies knew about these camps and their exact locations remained a mystery to us. After all, in Mongolia, 50% of the population still live the nomadic life for at least part of the year (an estimated 25% are full-time nomads) and move with the changing of the four seasons. To make things even more complicated, there are no regulations or laws and thus these families pitch their gers anywhere in the vast and empty countryside.

Some of these families tried to improve the living conditions in their camps by fetching huge canisters of water every other day to wash themselves and their cloths, to do dishes and to cook. One family's dad had even built a shower in one of the gers. This man was the only one who had put some thought into improving his family's and his guests' hygienic situation by building an actual shed for a pit latrine that he kept spotlessly clean and surprisingly non-smelly. Most other families, however, didn't seem to care that much. Most of the time they had dug a whole in the open field that was more or less deep and thus more or less overrun with human excrements, used hygienic products for the women's time of the month, shreds of toilet paper and dirty diapers. We came to prefer those facilities that did not have a shed built around them as they didn't keep the smell inside. Some of them were so bad that we actually preferred walking into the open field until the camp was out of sight and doing our business with a 360° panoramic view of the Mongolian emptiness.

It was the most confusing thing for us: these people had been living in the steppes for thousands of years and yet they had hardly put any thought into improving their living conditions. When we headed north for the Russian border it was already end of August and temperatures fell below zero at night. Still the only way to not freeze to death in the gers was to start a fire in a little metal stove. This turned the gers into a sauna for about an hour. Once the wood burned down the temperature fell back to around zero within minutes. In many gers the temperature was even lower after the fire had burned down: in order to not suffocate, the Mongolians attached a chimney to the stove that required the ger's roof to remain partly open. It was a truly inconvenient and ridiculous appliance that spoiled the last days of our tour as Lea fell ill.

After visiting Iran and seeing how the people there had spent hundreds of years improving the architecture of their buildings, eventually making it possible to heat a Hamam up to sauna temperatures using nothing but the flame of a single candle, the Mongolian's apparent lack of interest to improve their living conditions was plainly weird. They tended to their livestock of often more than a thousand sheep, goats, horses, cows, yaks and camels by hand - a full time job of 17 hours per day, seven days a week. And even though they lived tremendously close to nature the nomadic families produced a large amount of trash that they disposed of by throwing it into the wilderness without the hint of a care.